On May 27, 1896, the looming storm above St. Louis swirled toward the ground. Ears popped and hairs raised as the air pressure dropped and the atmosphere filled with static electricity. Big drops of rain fell down, then sideways as winds picked up and spun. The tornado was on the ground for only 20 minutes but damaged thousands of buildings across a ten-mile path. In total, 255 people were killed, making it the deadliest event in St. Louis history.

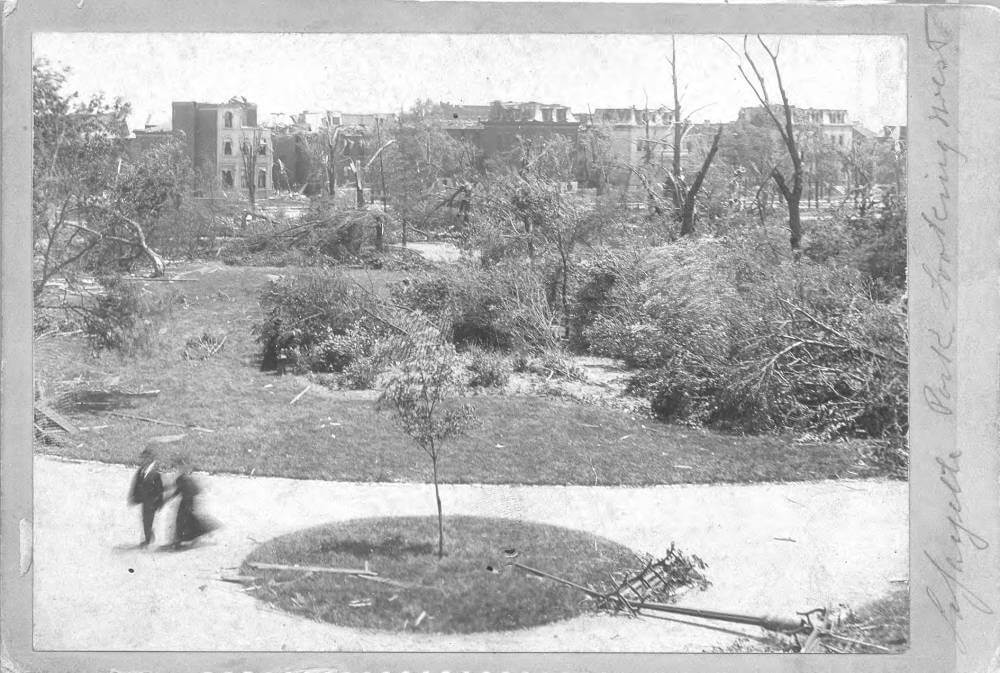

Some of the most severe destruction occurred in Lafayette Park. Photo via the St. Louis Public Library’s Digital Collections.

Some of the most severe destruction occurred in Lafayette Park. Photo via the St. Louis Public Library’s Digital Collections.

In the early days of the “San Luis” settlement, the land where Lafayette Square now stands was nothing but grazing ground for village livestock. Missouri was the wild west and travelers through this underdeveloped grassland were frequently ambushed by bandits. The St. Louis mayor’s solution circa 1830 was to transform the place into something valuable.

Thirty acres were designated under the city ordinance for public recreation. This pre-Civil War park was the city’s first, the frontier’s first, and the birth of the Lafayette Park folks still enjoy today. The name is a tribute to America’s Revolutionary hero Marquis De Lafayette.[i]

Within 30 years, Lafayette Square was as fashionable a place to live in as it is now. This period saw a 900% population boom across the city, and prominent St. Louisans bought up the land around the park to take up residence next to the nation’s newest urban Eden.[ii] In 1877, the St. Louis Dispatch published a letter from a recent visitor that opened as follows:

“[St. Louis] should feel proud, for every stranger coming into the city and visiting its many beautiful resorts will manifest a pride over the fact that Lafayette Park is the property of a city in the United States.”[iii]

The first evidence of the neighborhood’s decline appeared around 1890. The city had been expanding west, and the suburbs caught the eye of newcomers. The now aging urban environment was falling out of style, and then, catastrophe.

When the neighborhood was most vulnerable, the storm remembered as “The Great Cyclone of 1896” leveled Lafayette Park. While tornadoes form over land and cyclones over water, this tornado was so powerful it in fact crossed the river into East St. Louis, earning it the exaggerated title.

With hundreds of buildings demolished and the park maimed, rebuilding was going to be a long and arduous process. Attempts were made at restoration, but the western exodus had already begun.

With demand in the tank and storm recovery sure to last decades, properties around the park sold for cheap. Buildings were renovated as rooming houses, hosting several families at once alongside drifters and short-term renters. History doubled down in 1929 with the Great Depression, and any hopes of resurrecting the glory days were dashed.

After World War II, exhaustive urban redesign came into focus. City planner Harland Bartholomew drafted the infamous “Comprehensive Plan for St. Louis” that deemed the Lafayette area obsolete and recommended it for destruction. [iv]

The neighborhood escaped demolition but continued its descent into disrepair. Crime was rampant in the 50s and 60s, and the reputation around the park was as bad as it had ever been. [v]However, the tides were ready to change again.

Anyone who was there will tell it the same way: a bunch of people with an affinity for old houses took a chance. A group of inspired individuals saw the potential embedded in the neighborhood’s infrastructure and took matters into their own hands.

The Lafayette Square Restoration Committee was founded in 1969 as St. Louis embraced the counterculture revolution of the decade. Lafayette Square real estate was cheap in 1970, and well-meaning self-starters could buy a property (or two or three) and spend the next few years overhauling it into something they and their neighbors were proud of.

Lafayette Square represented, in a word, opportunity. On the surface, homes were dilapidated; rundown; properties one could kindly call “fixer-uppers”. To those who could see past the surface, however, the emphasis was on “upper”. Homes near the park, as austere as they were, were good investments. A home that sold for $3,000 then may go for as much as a million today (with a few decades of gumption built into it, of course).[vi] It could happen anywhere, as long as there are people willing to invest that energy.

Today, Lafayette Square is a weathered, contemporary form of its 19th-century self: beautiful, stylish, elegant, and storied. Like the city it helps compose, the Square is a combination of rich historical infrastructure and abiding vigor. It faced near-total destruction and yet it grew back. Like its origin, Lafayette Square’s revitalization came from people choosing to cherish the place where they live.

References

[i]http://umsl.edu/mercantile/events-and-exhibitions/online-exhibits/missouri-splendor/urb_Lafayette_Square.htm

[ii]http://umsl.edu/mercantile/events-and-exhibitions/online-exhibits/missouri-splendor/urb_Lafayette_Square.htm

[iii] https://lafayettesquare.org/1875-the-lafayette-square-hotel/

[iv] https://nextstl.com/2021/04/harland-bartholomew-destroyer-of-the-urban-fabric-of-st-louis/

[v] https://lafayettesquare.org/1967-tales-from-two-lafayette-square-pharmacies/

[vi] https://www.riverfronttimes.com/stlouis/lafayette-square/Content?oid=31665456&storyPage=2