The ancient people who first walked the ground that now makes up East St. Louis left us no record of their name.

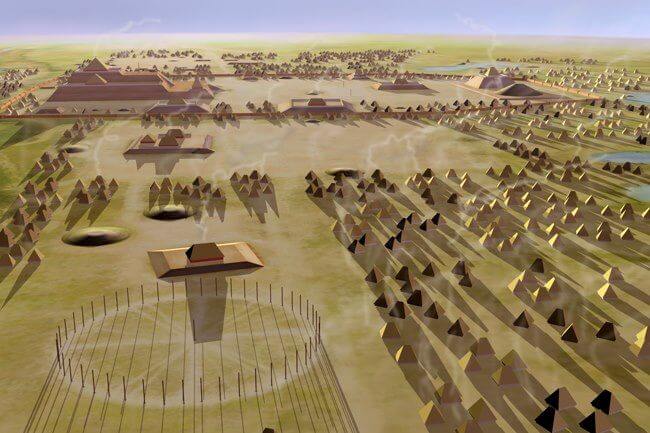

In 1050 CE, when the Mississippian city grew from the riverside settlement it had been for ten millennia into the metropolis of 15,000 people we remember it for, it wasn’t called “Cahokia”. It was called… well, we have no idea.

For the unacquainted, Cahokia is a historic site in present-day Collinsville, Illinois (about a half-hour from St. Louis). There once stood an early American example of urbanization. “Cahokia” is in fact the name of the people who were living there when it was discovered by Europeans hundreds of years later, but they were not its founders. It is described as prehistoric because, as far as we can tell, they had no written language whatsoever. With no historical record to speak of, we broadly termed the city’s inhabitants “Mississippians”, referring to centuries of peoples living along the Mississippi River.

Modern development across the globe was made possible through writing: it streamlined communication, expanded expression, and enabled the collection and preservation of information (books, records, headstones). Functioning without writing is incomprehensible today, but that hasn’t always been the case. The Cahokian oral tradition was sufficiently refined to construct one of the largest civilizations the continent had ever seen.

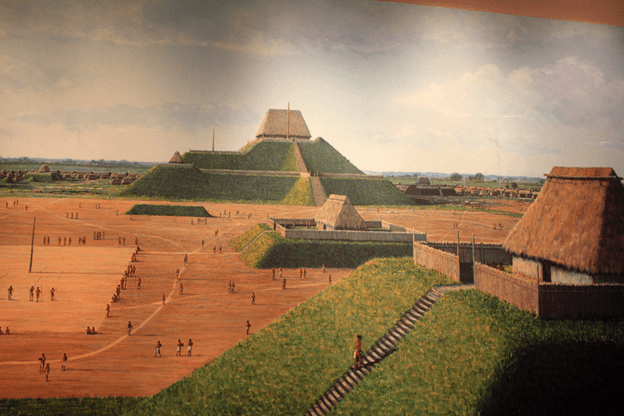

If you’ve heard of Cahokia, you’ve no doubt heard of its “mounds”. While not inaccurate, the term “mound” doesn’t exactly inspire awe in the way “pyramid” or “cliffside pueblo” does. Despite the unexciting term used to describe them, the biggest Cahokia Mound, located in the city’s center, and where the central governmental temple stood, is the largest prehistoric earthwork in the western hemisphere. Monk’s Mound is bigger than the Mexican Pyramid of the Sun, and at its base, Monk’s Mound covers somewhere between 13 to 15 acres—larger than the base of the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Core drillings revealed that the great dirt butte was constructed in layers over a century by means of carrying more than 14 million individual baskets of clay and soil. Some of the mounds contain wooden frameworks and their function was mainly to elevate important buildings, though some are burial mounds.

Some believe that Cahokia is built guided by the cycles of the sun, which they tracked with solar calendars known as Woodhenges. Composed of wooden posts arranged in a circle, a Woodhenge marks the sunrise on the solstices and equinoxes with each post, as well as other agriculturally significant events, allowing people to measure time and mark growing seasons.

One of the larger Woodhenges was excavated about half a mile west of Monk’s Mound, the peak of Cahokian ceremony and religion. Each equinox, someone standing at the center of this Woodhenge would notice that the post marking the sunrise also aligns perfectly with the front of Monk’s Mound. The striking view makes it appear as though the sun rises directly from the earthen mass.

The remarkable sophistication of this prehistoric city and society begs the question “How?” Engineering details aside, the fundamentals are obvious: Cahokia was built on extreme resolve, patience, and reverence for something greater than the individual.

Even though we do not know their proper name, the original Cahokians made a name for themselves. The spirit required for generations to devote enormous manpower to unprecedented construction projects and celestial precision had roots in faith, but more tangibly, it was commitment to community. The anonymous people who walked this very ground left us no record, but they left us lessons in the simple form of dirt mounds.