In 1673, during the first European expedition of the Mississippi River region, explorers Louis Jolliet and Father Jaques Marquette’s party came across a bluff painting which they described as follows:

“…We saw two painted monsters which at first made Us afraid, and upon Which the boldest savages dare not Long rest their eyes. They are as large as a calf; they have Horns on their heads Like those of a deer, a horrible look, red eyes, a beard Like a tiger’s, a face somewhat like a man’s, a body Covered with scales, and so Long A tail that it winds all around the Body, passing above the head and going back between the legs, ending in a Fish’s tail.”

Although the original pictograph that they described disappeared from the cliff for many years, the memory of the Piasa never faded, and the mural was revived in the early 1960s. As a proposed alternative to the frequent repainting of the mural when it would naturally fade, in 1984 the Alton-Godfrey Rotary Club sourced a 40-foot-long painted piece of steel depicting the iconic cryptid to mount on the bluff at Norman’s Landing.

The steel cutout installed in 1984

This installment was retired after only about a decade and it now stands at the end of the football field at Southwestern High School in Piasa, IL, providing an impressive representation of the school’s mascot. In 1998, Alton, IL established Piasa Park and the bluff painting was renewed once again. Since then, regular maintenance on the bluffs ensures the Piasa never stops gazing over the river it began guarding centuries ago.

When Joliet and Marquette’s party first encountered the painting, they were frightened—was it a warning? A threat?

Father Marquette’s account is the earliest written record of the Piasa pictograph, but the painting was a historical record in and of itself. Mississippian Native Americans had no written language at this time and instead preserved history through oral tradition and pictographs just like this one.

Thanks to the unrelenting research of recent scholars from the East Central Illinois Archeological Society, the origin of Piasa’s name and the legend it most likely emerged from seems to finally be clarified.

However, in the absence of a clear origin story for decades, an 1836 story published in The Family Magazine is what appears to have played the biggest role in influencing the legend that was passed down through generations, as well as the image of the “monster” as it exists today.

As recent research has shown, the Piasa that was originally painted on the bluff was most likely a version of what archeologists have called the “underwater panther” theme that appears across petroglyphs, pictographs, and objects made by the many tribes that populated the continent, from the Great Lakes in North America, down to the Andes in South America.

In this case, a Peoria Tribe legend recently translated by the foremost expert on Miami-Illinois language, David Costa, and told originally by a member of the Peoria Tribe to the Smithsonian Institution, might provide the most accurate tale that gave origin to our Piasa.

This legend tells the story of Wiihsakacaakwa, a trickster not unlike others that feature in many mid-continent native tales meant to teach us valuable lessons of how to live the right way. Wiihsakacaakwa and a Frenchman embark on a boat journey and come upon a cave known to be the home to a man-eating manitou. In true trickster form, Wiihsakacaakwa decides to be as obnoxiously loud as possible, ignoring the Frenchman’s fearful pleas to stop.

Inevitably, the manitou emerges and sucks the boat into its den, where they find other people were being held captive and slowly eaten by the monster. After the beast goes to sleep, Wiihsakacaakwa instructs his fellow prisoners to escape, while he loads the manitou with gunpowder to later blow him up. Having defeated the beast, Wiihsakacaakwa makes the den his home for a little while, until a set of malevolent twin dwarfs, referred to as “payiihsaki,” emerge to steal the den from him.

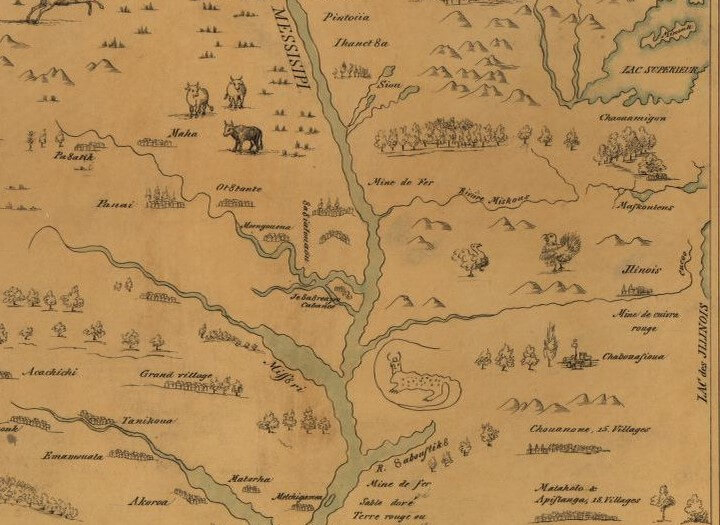

This legend, along with the maps created in the late 1600’s shine a light on two pieces of the puzzle. The first is that the name Piasa likely originates from the Miami-Illinois word “payiihsa”, often used in reference to small supernatural creatures. The second is that the appearance of the original Piasa likely did not feature wings. As many maps, including the 1682 map of the Mississippi below shows, a wingless creature whose features almost perfectly match those described by Jolliet and Marquette’s written account marked the spot where it rests even today.

Section of 1682 Map of the Mississippi by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Franquelin and Louis Joliet, Library of Congress

The mural as it exists today painted by Dave Stevens of Godfrey, IL

The presence of the mural today is a gift, and often, the best expression of gratitude is to pay it forward. That is why the maintaining of the Piasa by the City of Alton is so important: telling history’s stories strengthens the thread of what makes up a community’s unique identity. Even when history must sometimes be rectified, history helps us shape our future with the lessons of those who came before us.