When Eliel and Eero Saarinen, father and son Finnish-American architects, were working on their competing designs for a landmark that would redefine the St. Louis skyline, there was barely a wall separating them.

Eliel was already a distinguished architect among the 172 who submitted designs for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial in 1947. His son, Eero, was an acclaimed designer in his own right, but at 38 years old was still working at his father’s firm.

This contest was an opportunity for Eero to set himself apart with a simple yet daring design—an opportunity which was briefly jeopardized by a miscommunication.

In the 1930s, St. Louis city leaders launched a project to commemorate those behind the western expansion of the United States. Chief among those honorees was Thomas Jefferson, who signed the Louisiana Purchase, doubling the size of the country and stretching out a vast frontier that would reshape America in both geography and philosophy.

At that time, St. Louis was the last major city before that frontier, which earned it the moniker of, “The Gateway to the West.” Ninety acres on the Mississippi River were designated for the site of the memorial commemorating Jefferson, as well as the likes of Lewis & Clark who completed their 8,000-mile voyage on the shores where the memorial was to be built.

The purpose of the memorial was “to keep alive in the present the daring and untrammeled spirit that inspired Thomas Jefferson,” it said in the original competition booklet, “the spirit that moved pioneers and heroes of thought and action from all over the world to press westward with a constructive energy and courage scarcely equaled in history; the spirit that conceived and made possible the territorial integrity and national greatness of the United States of America.”

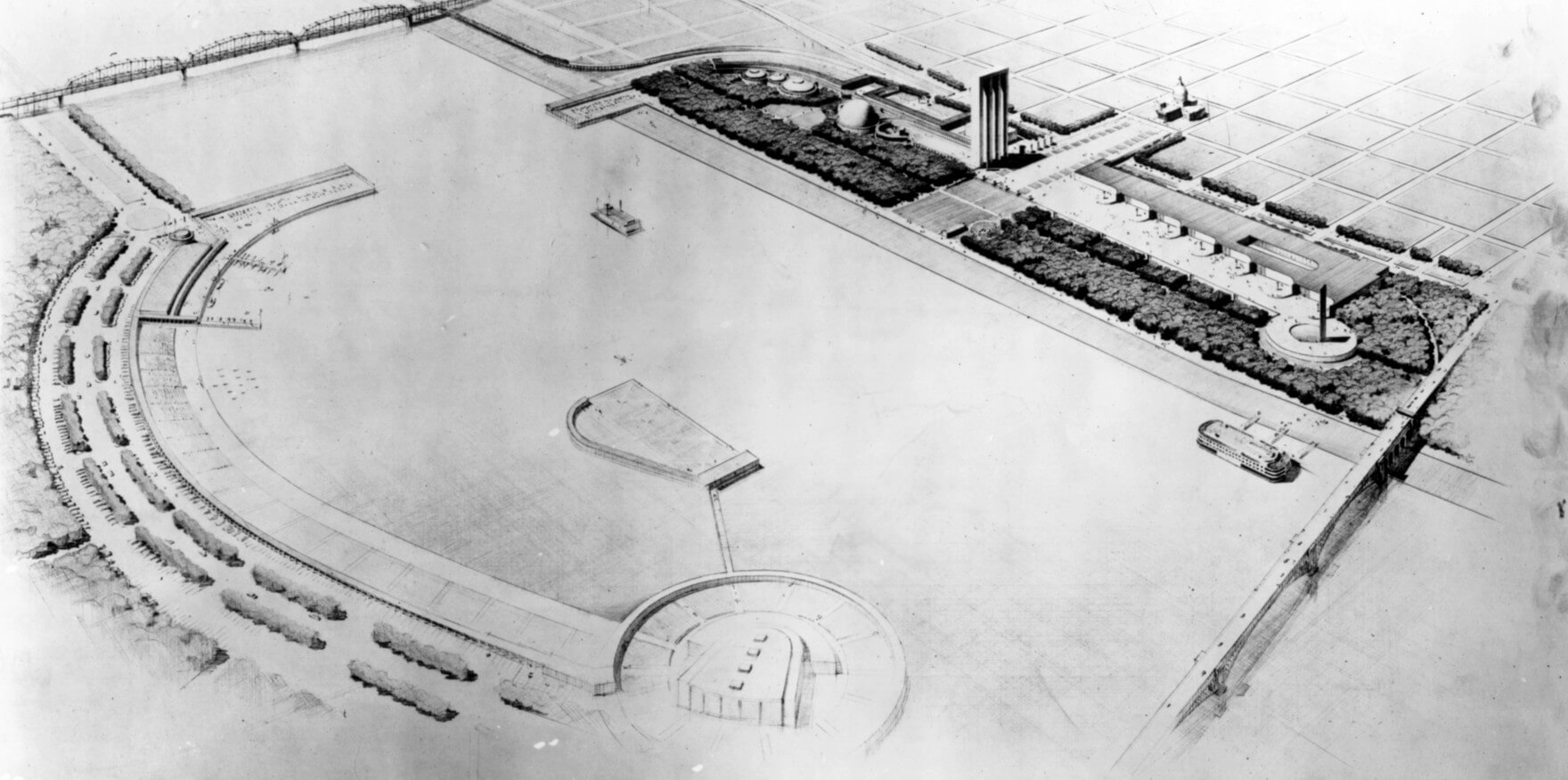

Eliel’s design was grand. The monument, which was part of a broader reimagining of the waterfront, consisted of four parallel concrete pillars hundreds of feet high, positioned perpendicular to the banks of the Mississippi.

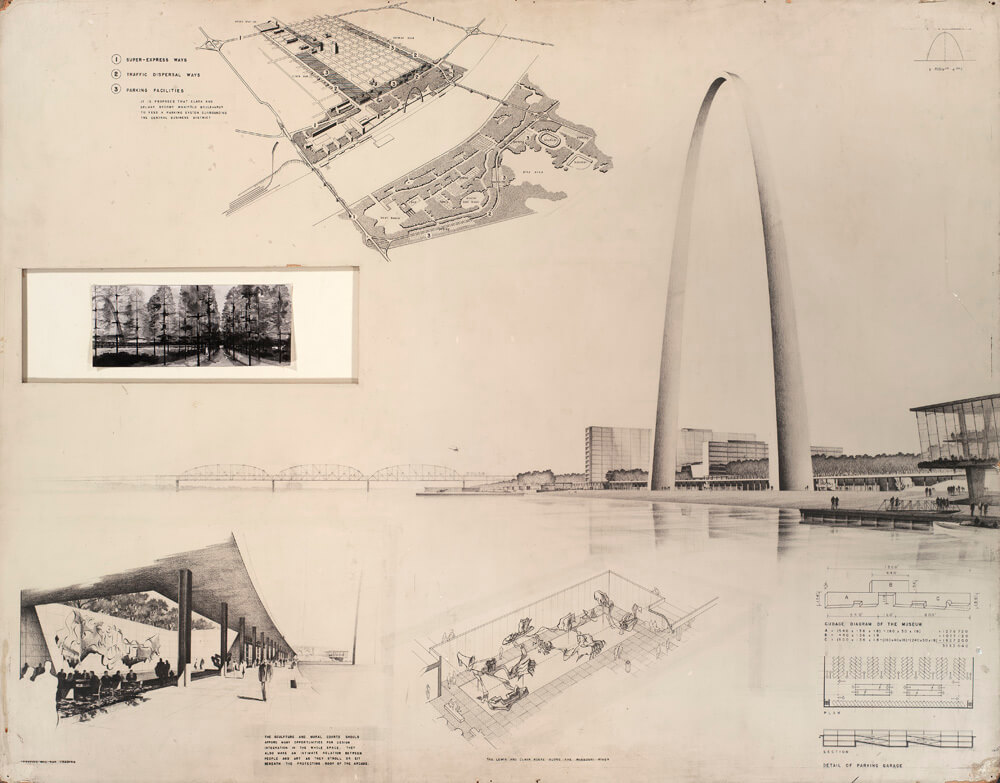

Eero’s design was another caliber of daring. He proposed a massive arch, parallel to the water as if framing the west of the country beyond it—a gateway. While the architectural demands were high and the execution needed to be extraordinarily precise, the design overcame the judges’ initial apprehensiveness about its feasibility.

All submissions were anonymized to ensure each was evaluated impartially. The seven-person jury identified 41 contenders on which they each voted. Eliel’s design was one of six that received two “yes” votes to advance as a finalist, but Eero’s design was one of just two that received six “yes” votes from the judges.

The name corresponding to the front-running entry: “E. Saarinen.”

By mistake, Eliel was notified by telegram that his design had been chosen as a finalist. There were three days of celebration at his architecture firm before a correction was issued. The family was reportedly in the midst of enjoying champagne when they received news of the error at which point Eliel, gracious in defeat, broke out a second bottle of champagne to toast to his son.

Following an additional round of revisions and evaluations among the five finalists, Eero’s Gateway Arch was unanimously chosen as the winner.

Eero’s star continued to rise after that as he joined the pantheon of modernist American architects. Sadly, he never got to see his greatest design realized. He passed away in 1961 at just 51 years old, two years before construction began on the Gateway Arch.

His vision not only captured but helped define the American ethos. True to purpose, it embodied the same ambition, creativity, and grit that moved Americans westward and into a new era.